Reading a first novel by an old friend is always a somewhat trepidatious experience for any writer. There’s the anticipation and excitement, of coursethe hope that the book will be awfully good, and will do well, and then you can mooch off your friend for drinks at any given convention. But less often spoken of is the fearthe risk that you won’t like the book, or worse, that it will be “a unbudgeable turkey.”

There’s the risk that you’ll find yourself saying things like “I really liked your use of weather imagery in chapter 3,” and praying that the friend doesn’t figure out that you never got past chapter 4.

This fear can be ameliorated by familiarity with short work by the same author. If you know your friend rocks the shorter narratives, there’s more advance evidence that the book will probably be okay. The anticipation can outweigh the dread.

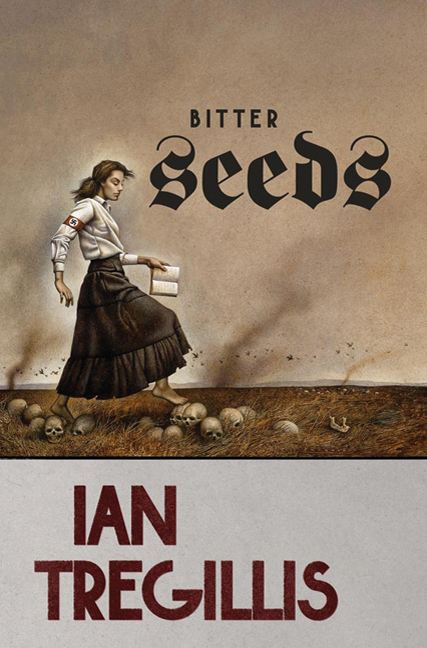

On the strength of prior acquaintance with his short work, I’ve been anticipating Ian Tregillis’s Bitter Seeds for Some Time Now, and I am pleased to report that no dread is indicated or required. In fact, this book is really very good, and I don’t just mean “good for a first novel.”

Tregillis has journeyed into that most overtilled field, World War II alternate history, and in the process he has created a unique, unsettling, and deeply atmospheric setting; populated it with a diversity of grimly fascinating characters; and turned up the heat with the sort of plot that requires those characters to keep shoveling frantically if they are ever to stay in advance of the needs of the firebox.

Bitter Seeds takes place in a Europe where America never entered the Second World War. Where England, embattled, turned to blood magic to defend its borders from invasion. Where Germany’s attempts to create an Übermensch bore fruit in the form of telekinetics, invisible women, men of flameand Gretel, the terrifying, sociopathic, precognitive master weapon of a master race.

But the Germans’ methods for creating their supermen are inhuman in the extreme, and the methods of England’s warlocks are worse, and by book’s end both sides will have paid prices they only begin to understand the horror of.

These are the book’s strengthsits atmosphere, its setting, the vividly imagined consequences of immoral and desperate actions.

It does have weaknesses as well, like any novel. The astute reader will have noticed that I have only mentioned one character by name, and she an antagonist. This is because, while our viewpoint charactersMarsh, Klaus, and Willhave distinct personalities, they are all very much at the mercy of events, and because of this they often seem to fail in having much of an agenda. It’s thematic that they all commit atrocities (and I use the word advisedly); it’s also thematic that these atrocities alienate the reader from all three of them.

I greatly admire Tregillis’s strength of purpose in allowing his characters to suffer the full impact of their immorality. It does, however, mean that it’s hard to find somebody in the story to root for.

Of course, Nazis are the great get-out-of-jail-free card of Western literature; if you have no one else to pull for, you can always root against the Nazis, and I also admire Tregillis for not making the situation as uncomplicated as all that. Klaus and his (slowly emergent) conscience are one of the high points of characterization in the book.

Also, as a female reader, it’s always a little odd for me to read a book in which the male perspective is exclusive, or nearly so, and in which male characters are largely motivated by their feelings for women (sisters, wives, daughters) who are in large part ciphers to the point of view character and therefore to the reader. It’s true to the time period, of course, and it seems true, in many respects, to the Western male psyche (inasmuch as there is any such monolithic thing, which is to say, maybe not so much), but the perception of women-as-admired-other is always a little hard for me to wrap my head around.

I suspect this will change in later volumes, and Gretel certainly has her own agenda. I imagine its uncovering will eventually become a question of tantamount importance.

All in all, this is an excellent first book, and I am eagerly awaiting number two.

Elizabeth Bear writes book reviews when she is procrastinating on her novel.